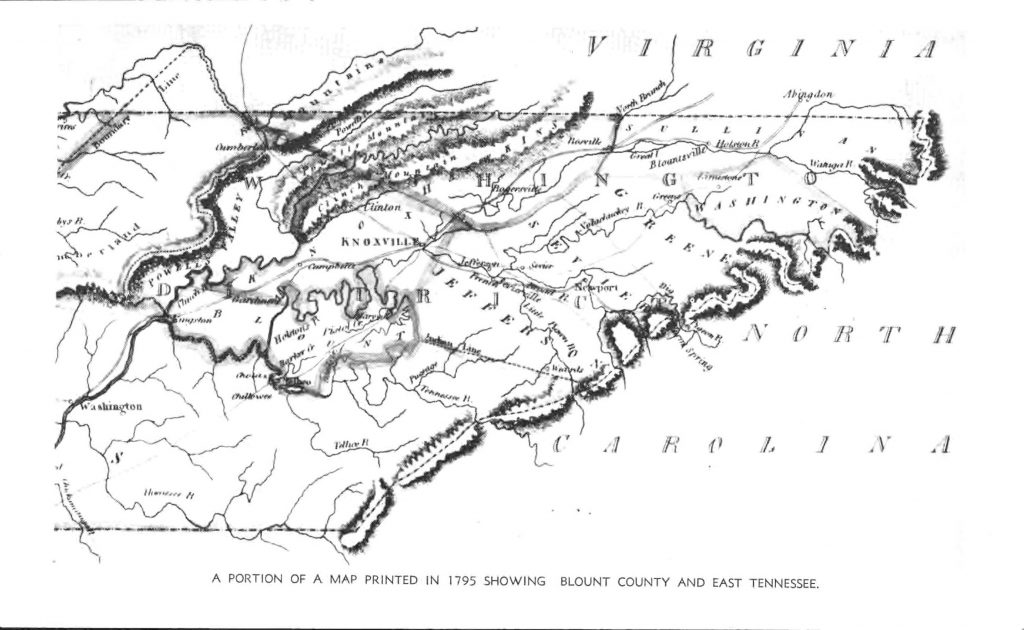

Blount County was created out of Knox County by an act passed at the second session of the territorial assembly at Knoxville, on July 11, 1795, and named in honor of William Blount, the first and only territorial governor. 1 Knox County had been created from fractions of Greene and Hawkins counties in 1792. 2 Greene was created from Washington in 1783, 3 and Washington was established in 1777, the oldest county in the state. 4 Since the creation of Blount County in 1795, the territorial limits have been added to by the Treaty of Tellico, 1798, and Calhoun’s Treaty of 1819. A portion was taken into Loudon County upon its creation in 1870. 5

Although Blount County was not established until 1795, the first settlement by white people took place more than a decade before, around 1782 or 1783. 6

In order to understand the history of the settlement of the section which became Blount County, it is first necessary to know something of the geographical position of the county. A glance at the map will show that it is bounded on the east by Sevier County (which has as its northern boundary the French Broad River) and the Great Smoky Mountains; on the south by the Little Tennessee River; on the west by Loudon County; while the Tennessee River forms almost all of its northern boundary, dividing it from Knox County. Thus all of the region comprising the present counties of Blount and Sevier is south of the French Broad River, a region which has had “a singular and remarkable history. 7

At the time that the first settlement of this region by white people took place, all of what is now Tennessee was a part of the state of North Carolina. The Revolutionary War was drawing to a close, and only two years before, in 1780, a great many of the men from the upper settlements in Washington, Sullivan, and Greene counties had taken part in the Battle of King’s Mountain, and only two months after that some of the same men took part in the Battle of Boyd’s Creek, 8 located in present Sevier County.

The route followed by Colonels Arthur Campbell and John Sevier in the Boyd’s Creek campaign was over the Great Indian Warpath which led through the entire length of Blount County to the Cherokee Indian towns on the Little Tennessee River. It was the same route which had been followed by Colonel William Christian in the campaign of 1776 against the Cherokees, 9 and again used by Sevier in the later Indian campaigns.

After the Revolutionary War ended there followed a period of difficulty between the United States and several states over the matter of the state’s western lands, which the United States wanted the states to cede to Congress. In 1783 North Carolina passed a law which opened its western lands and established a land office for their entry and purchase. By this act the land below the French Board River was reserved to the Cherokee Indians as hunting grounds. The act also prescribed a penalty for anyone who made entries or surveys on the lands south of French Broad; however, North Carolina did make some grants in the reservation and received money from the grantees.’ 10

As early as 1782 there were complaints by the Indians about the settlers on their lands south of French Broad. In a letter to Colonel John Sevier, dated February 11, 1782, the governor of North Carolina wrote: “I am distressed with the repeated complaints of the Indians respecting the daily intrusions of our people on their lands beyond the French Broad River. 11 The Governor instructed Sevier to warn the intruders and if they did not remove to drive them off by force.

On June 2, 1784, the North Carolina legislature passed an act for the cession of its western lands subject to the conditions that North Carolina should satisfy her soldiers’ claims, and that all entries to land she had authorized should be recognized, and that a state or states should be formed from the territory. 12 The United States Congress was given one year to accept the cession.

The State of Franklin

When North Carolina closed the land office set up under the act of 1783, 13 as a result of the act of 1784, a furor went up in the western country. Leaders from the various counties took steps to form a government which resulted in the State of Franklin. 14

At the first session of the legislature of Franklin, which ended on March 31, 1785, among the several acts which were passed was one called “An Act to divide Greene County into three separate and distinct counties, and to erect two new counties by the name of Caswell and Sevier. 15 The historian Ramsey thought that Caswell “occupied the section of country which is now Jefferson, and extended probably west . .. extended down the French Broad and Holston to their confluence, and perhaps further west. . . . The other new county embraced what is still known as Sevier County, south of French Broad, and also that part of Blount east of the ridge dividing the waters of Little River from those of [Little] Tennessee.” 16

There is good reason to believe that a Blount County of the State of Franklin came into existence at this time, for in the Pennsylvania Packet of January 5, 1786, under the heading of “State of Frankland, August Session, 1785,” a call was made for the inhabitants to elect members to a convention to consider the cession act of 1784, “in the following numbers for each county, viz. Washington, 15; Sullivan, 12; Green [sic], 12; Caswell, 8; Severn [ Sevier], 6; Spencer, 5; Wayne, 4; Blurt [probably Blunt, for Blount], two. .. .”

Meanwhile, John Sevier and other officials of Franklin had negotiated the first of two treaties with the Cherokee Indians. This first one was held at the mouth of Dumplin Creek, on the north bank of French Broad River (in present Sevier County) on May 31, 1785. The treaty fixed the ridge dividing the waters of Little River from those of the (Little) Tennessee as the dividing line between the possessions of the whites and the Indians. The Indians ceded all claim to lands south of the French Broad and Holston (Tennessee), lying east of that ridge. [Italics mine.]

The other treaty or conference was held at Chota Ford and Coyatee, on the Little Tennessee River, from July 31 to August 3, 1786. The boundary between the whites and the Indians was fixed at the Little Tennessee. 17

In November of 1785 the United States had negotiated the Treaty of Hopewell with the Cherokees. Article Five of this treaty provided:

If any citizen of the United States, or other persons, not being an Indian, shall attempt to settle on any of the lands westward or Southward of the said boundary [French Broad River] which are hereby alloted to the Indians for their hunting grounds, or having settled will not remove from the same within six months after the ratification of this treaty, such persons shall forfeit the protection of the United States, and the Indians may punish him or not as they please, provided that this article shall not extend to the people settled between the fork of French Broad and Holston Rivers, whose particular situation shall be transmitted to the United States in Congress assembled, for their decision thereon, which the Indians agree to abide by. 18

Under the Treaty of Dumplin most of the earliest settlement of Blount County took place, the settlers following the route of the Great Indian Warpath and establishing their homes along the many streams which drain the county. By 1786 there were enough settlers to form two Presbyterian congregations, New Providence, 19 at Craig’s Station, the site of the present city of Maryville, and Eusebia, located near the head of Boyd’s Creek, in what became known as the “Bogle Settlement.” 20

By March, 1787, it is known that the State of Franklin had opened a land office for the purchase of lands in the tract south of French Broad, but there are no surviving records to show who purchased lands; however, it is known that the land was sold at forty shillings per hundred acres in furs, ten shillings “in hand,” and two years’ credit for the other thirty shillings. 21 There are a few scattered records in the public records of Greene County which contain names of individuals known to be living in Blount County at the time 22

The State of Franklin was never recognized and died out in 1788; therefore, the treaties of Dumplin and Coyatee were not valid, and the settlers on the lands south of French Broad River were considered encroachers on the Indian lands. Since they were outside the limits of any government, they set about to organize some system of governing themselves. Representatives of the inhabitants met on January 12, 1789, and framed the “Articles of Association,” by which they were presumably governed until the Southwest Territory was established. 23

Establishment of Land Rights within Blount County

Beginning in 1787, when by another proclamation the settlers were ordered off these lands, there began a series of Indian attacks. For their protection the settlers built small fortifications known as stations to which the outlying settlers might flee for protection in time of attack. Those within the present limits of Blount County were Gamble’s, Houston’s, Henry’s, Ish’s, Kelly’s, Bird’s, Craig’s Black’s Calvin’s, Well’s, and Gillespie’s. 24

In 1789 North Carolina did cede her western lands to the United States. One section of this act provided:

That this act shall not prevent the people now residing south of French Broad, between the rivers [Little] Tennessee and Big Pigeon, from entering their pre-emptions on that tract, should an office for that purpose be opened. . . . 25

The Territory South of the River Ohio was established in 1790 by the United States Congress, with William Blount as governor. One of the earliest official acts which Blount undertook was to negotiate the Treaty of Holston with the Cherokee Indians, which he did at Knoxville, on July 2, 1791. By the provisions of the treaty “a line was established, to the south of which the Indians were to withdraw and beyond which the settlers were not to encroach.” This line became known as the Indian Boundary. “That section of the line crossing East Tennessee was described in the treaty as beginning on the North Carolina boundary at a “point from which a line extended to the river Clinch shall pass the Holston [ Tennessee] at the ridge which divides the waters running into the Little River from those running into the Tennessee [Little Tennessee]’.” 26 The location of the line was uncertain, and it was not surveyed until 1797. Meanwhile settlement advanced and pushed the location southward.

In 1792, when Knox County was established, it included all of the territory which became Blount County in 1795. Many of the early Knox County officials appointed by Blount were men living in what was later Blount County, and most of them were appointed to the same office by Blount when the new county was organized. 27

1795 Act of the Territorial Assembly

The act which created Blount County described its bounds as:

Beginning upon the south side of the river Holston [Tennessee], at the mouth of Little River, then up the meanders of Stock Creek upon the south side to the head of Nicholas Bartlet’s mill pond at high waters, thence to a direct line to the top of Bay’s Mountain leaving the house of James Willis to the right, within forty rods of the said line, thence along Bay’s Mountain, to the line of the county of Sevier, thence with that line to the eastern boundary of the Territory, thence southwardly to the line of the Indians according to the treaty of Holston, and with that line to the river Holston [Tennessee], and up the meanders of the river Holston [Tennessee], upon the south side, to the beginning. . . . 28

The act also provided that a court of pleas and quarter sessions be established and that the first meeting take place at the home of Abraham Wear, William Wallace, Joseph Black, Samuel Glass, David Craig, John Tremble (Trimble), Alexander Kelly, and Samuel Henry were appointed commissioners to fix the county seat by obtaining fifty acres of land and laying it out into a town “to be known by the name of Maryville,” no doubt, in honor of Mary Grainger, wife of Governor William Blount. The commissioners selected the site of Craig’s Station, and obtained fifty acres of land from John Craig. 29

The first court for the county met at the home of Abraham Wear on September 14, 1795, “Present William Wallas, William Lowry, Oliver Alexander and James Scott who produced Commissions of the peace from his Excellency, Governor Blount. . . .” 30 Other justices who appeared were David Craig and George Ewing. William Wallace was appointed chairman of the Court; John McKee, clerk; William Wallace, register; Littlepage Sims, sheriff; Robert Rhea, coroner; John McKee, trustee. 31

Footnotes

- George Roulstone (comp.), Laws of the State of Tennessee (Knoxville, 1803), 60-61. Hereafter cited as Roulstone, Laws; William H. Masterson, “William Blount and the Establishment of the Southwest Territory, 1790-1791,” East Tennessee Historical Society’s Publications (Knoxville), No. 23 (1951), 3-31. The new county was made a part of Hamilton District.[↩]

- Roulstone, Laws, iv.[↩]

- Walter Clark (ed.), The State Records of North Carolina, 14 vols, continuing earlier series of Colonial Records (Goldsboro, 1905), XXIV, 539-40. Hereafter cited as N.C.S.R.[↩]

- Ibid., 141-42. The first tax lists of Washington County (1778) will be printed in this series.[↩]

- Acts of Tennessee, 1870, pp. 4-9 (Ch. 2). The original name of Loudon County was Christiana.[↩]

- Memorial of Tennessee Legislature to United States Congress (Nashville, 1806), copy in Legislative Papers, Tennessee Archives, Nashville. “That the settlements made on lands within the limits of this state, south of French Broad and Holston [Tennessee] and West of Big Pigeon rivers, commenced some time in the year, 1782 or 1783 . . . .” Until 1874 the present Tennessee River from the junction of the French Broad and the Holston, near Knoxville, to the mouth of the Little Tennessee, at Lenoir City, was known as the Holston, and the present Little Tennessee as the Tennessee. This is often confusing, especially in locating early sites, as the land in the calls of the early grants and deeds is usually located by water courses.[↩]

- Samuel Cole Williams, History of the Lost State of Franklin (New York, 1933), 218. Hereafter cited as Williams, Lost State.[↩]

- For accounts of these campaigns see Lyman C. Draper, King’s Mountain and its Heroes. . . (Cincinnati, 1881) ; J. G. M. Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century (reprinted, Kingsport, 1926). Hereafter cited as Ramsey, Annals; Samuel Cole Williams, Tennessee During the Revolutionary War (Nashville, 1944).[↩]

- Ibid, 48-60; Ramsey, Annals, passim.[↩]

- N.C.S.R., XXIV, 478-82.[↩]

- Ibid., XVII, 14-15.[↩]

- Ibid., 561-63.[↩]

- Ibid., 563-64.[↩]

- For a full, authoritative account see Williams, Lost State; also Ramsey, Annals.[↩]

- Ibid., 294.[↩]

- Ibid., 295.[↩]

- The texts of these treaties may be found in N.C.S.R., XXII, 649-50, 655-59.[↩]

- Charles C. Royce, “The Cherokee Nation of Indians: a Narrative of Their Official Relations with the Colonial and Federal Government,” in Bureau of American Ethnology, Fifth Annual Report, 1883-84 (Washington, 1887), 133-34, 153-58.[↩]

- Will A. McTeer, History of New Providence Presbyterian Church, Maryville, Tennessee, 1786-1921 (Maryville, 1921). Hereafter cited as McTeer, New Providence Church.[↩]

- Will A. McTeer, Eusebia Church History, Homecoming, August 31,1924 ((Knoxville, 1924]).[↩]

- N.C.S.R., XXII, 678.[↩]

- See footnote 41, below.[↩]

- These “Articles” are printed in Ramsey, Annals, 435-36; also in Williams, Lost State, 226-28.[↩]

- Ramsey, Annals, passim.[↩]

- Clarence E. Carter (ed.), The Territorial Papers of the United States, IV, The Territory South of the River Ohio, 1790-1796 (Washington, 1930), 6. Hereafter cited as Carter, Territorial Papers, IV.[↩]

- Mary U. Rothrock (ed.), The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee (Knoxville, 1946), 43. Hereafter cited as French Broad-Holston Country. The text is in Carter, Territorial Papers, IV, 60-67.[↩]

- Ibid., 449-50, 489-71.[↩]

- Roulstone, Laws, 60.[↩]

- Blount County Deeds (Courthouse, Maryville), Book I, 186, Book II, 29. Hereafter cited as Deeds.[↩]

- Blount County Minutes of Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions (Courthouse, Maryville; typewritten copy, McClung Collection, Lawson McGhee Library). Hereafter cited as Minutes.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]